First Annual Online Alla Prima Challenges

20 live painting alla prima sessions over 20 weeks (plus an introductory orientation) beginning on: January 12

WHEN: Thursdays – 2 pm to 3 pm EST. starting January 12th, 2023

Welcome to the official Smartermarx thread for the 2023 Online Alla Prima Challenges. Sessions will be carried out each Thursday at 2 pm EST. Each session will last about 1 hour, which includes 30-45 minutes of painting time (depending on the challenge for that week) and 15-20 minutes of discussion about the goals of the exercise and some tips to make the effort more successful. After each session, participants will have one hour to share a photograph of their effort in a shared Dropbox folder that will serve as a private learning gallery for all participants. Links to the folder will be made available in an email like this one that precedes the session.

Prior to the first painting session, I will be hosting an “Orientation” session on January 12th. This will serve as an introduction to the challenges, a walkthrough of the primary goals, what is needed to participate, the role of the Dropbox gallery, and a general Q&A to ensure everyone is ready to go on January 19th!

TO REGISTER: Please complete and submit the appropriate email sign up form on Anthony Waichulis’ website on this page: Online Classes and Events | Art and Articles

If you are interested in learning about each challenge ahead of time, you can see the full schedule here: Alla Prima Challenges. Also, if you are interested, Smartermarx has additional info on the general strategies that I often use to approach the alla prima (specifically the SNAG concept – Survey, Notan, Anchors, and Gradations.) If you wish to join us, please sign up today! (You can unsubscribe from the list at any time.) Please forward any additional questions to my administrator, Anya Dribas, at aaaw.anyadrs@gmail.com.

JANUARY 12: ORIENTATION

Here you will find all of the information (appropriate links (including Dropbox folder links for image sharing), notes, reminders, etc.) for The 2023 Online Alla Prima Challenges.

NOTE: Please respect the work, rights, and privacy of participating artists. You may view the efforts in in the following Dropbox folders from the sessions for educational purposes, but you may not download or manipulate their work in any way. All files in the Drobox folders will be deleted 2-3 weeks following each session. In addition, please know that live sessions, including questions and contributions from participants, will not be recorded to respect each participant’s experience.

Certain files may be included for participant usage (provided by Anthony or Anya and may be downloaded.) Such files will be indicated during the relevant live session.

Key points from Jan 12th orientation session:

- Please keep yourself muted during session unless you are part of an active conversation. Here’s 2 tips for quick muting/unmuting during zoom sessions:

- While muted, press and hold down SPACE when you want to talk. This unmutes you temporarily.

- Keyboard hotkeys for toggling mute:

-

• Mac: Command(⌘)+Shift+A

-

• Linux: Alt-A

-

• Windows: Alt-A

-

The primary goal with the sessions is illuminate the consequences of the fundamental components (concepts and actions) of your process by utilizing timed, narrow-focus challenges that can provide fast feedback and useful insights.

-

Sessions are not intended to be a demo series. This is a group activity that works best for both the group and the individuals when participants engage with the activity in concert. In addition, the series is not intended to instruct anyone to “paint like me,” but rather to analyze the fundamental components that make up YOUR process with short, controlled challenges.

-

While “I’d like to watch first then try it on my own–on my own time!”, may sound intuitively advantageous, in my experience, such a practice often leads to diminished returns. Again, the sessions are not designed to teach people to do something like I do it (although I am elated if any aspect of my process proves useful to you.) rather, this is about analyzing your own output, generated with adaptations of your own process, in a context that has been demonstrated to yield productive feedback.

-

If you are not sure exactly how to approach a specific aspect of the alla prima—don’t worry—just give it your best shot (using even a “best guess” if necessary.) We need to make mistakes or even an outright mess to find meaningful development. Avoiding experience will get you nowhere. Additionally, I find that it is often far more effective (in a learning context) to try and “modify,” add or delete a component of an existing process when the experience of the process and the relationship to the resulting product are fresh in your mind. Remember that experiences (especially what you might deem mistakes, errors, frustrations, etc.) will also cultivate the most useful questions for you that I hope we can answer together. (I’ve refer to this practice as “building an experience database.”

-

You should be ready to paint right when the session starts with you subject matter arranged and illuminated, your palette and brushes at the ready, and have the criteria for the session in mind.

-

When selecting, arranging, and lighting your subject matter, keep in mind the guiding principle in this context:

RECOGNITION MUST SURVIVE ABSTRACTION!

- Regarding pre-mixing rules: What this means is that you are forbidden from mixing locals or other observable “color notes” perceived within or around your subject. Such mixing should be done “on the fly” (i.e., as part of your painting time.) This limitation pushes you to exercise your intuitive or heuristic -based understanding of color dynamics. Pre-mixing limitations can also push one to experiment in a more cavalier manner with buffer or step colors (or chromophages) (which are colors that are added to a particular painted passage or transition to appear closer to the perceived transitions within your subject (often generated by illumination or reflectance properties.) It is very important to acknowledge and remember that observed transitions with your subject do not often map to a simple mixture of the obvious categorical components that may define the poles or anchors of the transition. For example, a transition that may be observed to evolve from a fairly bright yellow to black will likely not be matched by simply mixing a black and yellow paint. More colors will need to be involved.

-

Additionally, the pre-mixing limitation may push you to explore means of hitting certain perceived color notes with an analog application dynamic, surface topography, etc. that may move beyond what we would expect with simple pigment mixing.

-

SWITCH COSTS: One can find incredible advantages in efficiency and effectiveness with minimizing “switch costs” during their process. Simply speaking, switch costs are the time, mental and physical costs incurred when switching between different tasks. For example, I highly recommend that that palette arrangement is made consistent to avoiding “hunting for colors”, making sure you have enough paint out to avoid stopping to replenish the palette, keeping all required brushes within arms reach so you don’t have to break from your work time to retrieve them, etc… These things can aggregate to seriously impact a 30 minute exercise putting you at a great disadvantage. (This is a great example of how a 30-minute alla prima challenge can illuminate something that may be plaguing your day-to-day painting practices.)

-

PROXIMITY: I urge everyone engaging in these exercises (or any observational representation for that matter) to consider the the subject’s proximity to the representation target (canvas, panel, etc.) As we observe our subject, we attend to the things that we feel may best serve our end goal. However, as we turn from our observed subject to observe the target surface—the information garnered from the subject begins to fade from our iconic and short term visual memory and becomes subject to compensation or enhancement from our long terms memory which is incredibly imprecise. Iconic memory is the visual sensory memory register pertaining to the visual domain and a fast-decaying store of visual information. Iconic memory is described as a very brief (<1 second). Visual short term memory (VSTM) is a memory system that stores visual information for a few seconds so that it can be used in the service of ongoing cognitive tasks. Long-term memory (LTM) is the memory store that can hold informative knowledge indefinitely. However long-term memory is by far the most abstract and imprecise.

-

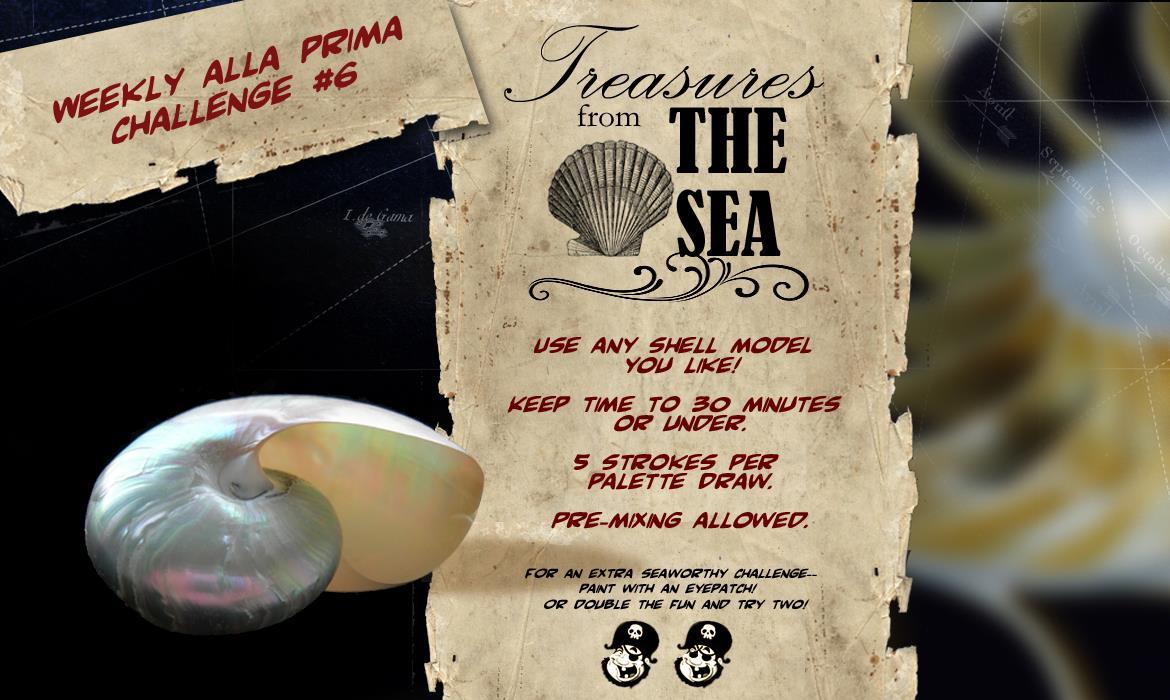

The palette draw rule means that after a certain number of brushstrokes you must pull more paint from the palette (reloading the brush) or you may void the brush altogether. This is done to ensure that you are not over-modeling the study relative to the challenge (i.e., unwarranted surface manipulation that leads to value/color contamination or excessive “blending” without drawing development or material application.) For example, a 5 stroke palette draw rule means that you can only apply 5 strokes before you must wipe and/or reload the brush—thus encouraging the artist think more “economically” and deliberately about brushwork. Additionally, the stroke rule should not be seen as a “minimum” number of strokes you must make prior to making a change to the brush—but rather, a maximum. Lastly, large homogenous regions, scrubbing, and early line work are all exceptions to the stroke rules unless otherwise stated (as they do not usually carry an immediate overmodeling or contamination threat.

*The dropbox link above that will be the locale for uploaded images following the Jan.19th session includes three files: 2 of them are examples regarding image size for uploading. The 3rd file is a SNAG poster which outlines the general approach that I use for approaching these challenges. I thought some of you may find it useful.

- A reminder newsletter will be issues via email each Monday with the Zoom link for the following session along with a description of the challenge so that you may acquire the subject needed as well as any other pertinent info.

Anthony’s Palette based on, or adapted from, a traditional double-primary configuration:

NEXT SESSION: JANUARY 19: