Thank you Sow and Orlando for the info. I’m only assessing the first page presented here as there are oceans of stuff to evaluate beyond it.

My heart goes out to you Sow as it is indeed challenging to navigate all of this information on your own. Hopefully this little exercise in analysis and evaluation will help you to better evaluate some of the resources at your disposal.

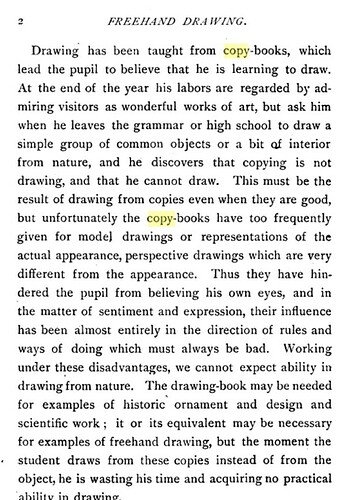

“Drawing has been taught from copy-books, which lead the pupil to believe that he is learning to draw . At the end of the year his labors are regarded by admiring visitors as wonderful works of art, but ask him when he leaves the grammar or high school to draw a simple group of common objects or a bit of interior from nature, and he discovers that copying is not drawing, and that he cannot draw.”

The term “drawing” can be used to describe a wide range of activities. It can be defined as simply as “a form of visual art or communication in which one uses instruments to mark paper or another two-dimensional surface.” Unfortunately, many authors try to sell a sort of privilege claim by engaging in what is called a “No True Scotsman” fallacy. There exists variations of this fallacy, but a very common form involves the exclusion of one or more members of a group via the altering of criteria as inclusion is likely to weaken the position of the person making the claim. For example:

Person A: “All great drawings are always done via observation from a live percept.”

Person B: “What about the many celebrated drawings that have been done from other sources like photographs, imagination, and construction?”

Person A: “Well those aren’t REAL drawings.”

Drawings can be evaluated by many types of criteria. Reference source is only one means by which one may choose to assign value.

The next major issue is the scenario put forward in an attempt to justify or validate the fallacy. So as it reads, the author states that since a student studied with a “copy book” he or she was never really learning to draw. The evidence is supposed to be found with the scenario in which said student could not “draw a simple group of common objects or a bit of interior from nature.”

This entire argument is ridiculously problematic. First, I don’t think I need to explain that effective learning sequences run in the direction of simple to complex. As such, the challenge of drawing a group of common objects or interior of nature would likely be approached long AFTER more simple, primary or foundational skills were acquired and cultivated so as to be applied forward. These may include a plethora of foundational mark (line, curve, shape and value) exercises. Even then, there are more foundational principles to address prior to effective percept surrogacy or representation (even simplified) involving principles and techniques for understanding the roles of observation, the nature of perception, the basics of illumination, etc. Therefore, do you think that it is reasonable to conclude that an individual studying foundational elements of drawing is not “really learning to draw?”

Well, let’s try and apply this to any other field. How about music? So if I spend a few months learning and practicing scales, arpeggios, and cadences, music theory, and simple melodies on a piano—learning from books—and then encounter great difficulty when jumping into Tchaikovsky (after only a year) can I assume that I wasn’t really learning the piano after all?

How about learning to read? Let’s say I spent my first year learning to read by sounding out letters, building reflexive word recognition, studying basic syntax rules, and plodding through Dick and Jane books. If, after a year, I cannot write my own novel or get through a Tolstoy, (or even Stephen King), is true that I was never really learning to read?

As you can see, this is a ridiculous argument.

The author continues, “This must be the result of drawing from copies even when they are good, but unfortunately the copy-books have too frequently given for model drawings or representations of the actual appearance , perspective drawings which are very different from the appearance.”

Sure, illustrations in books can indeed be wildly different from the experience of a live percept. However this is a false dilemma introduced as more “evidence” for the author’s position. This has no significant bearing (in this context) on the fact that a student cannot draw whatever they like after only a year of study. The reason is that development takes time and quality practice. Such realities are not merely the result of the fact that illustrations and live percepts appear different.

“Thus they have hindered the pupil from believing his own eyes, and in the matter of sentiment and expression, their influence has been almost entirely in the direction of rules and ways of doing which must always be bad.”

Ok, now this just gets plain stupid. Every activity we engage in is defined by conventions or rules. To argue that to move in the “direction of rules” is always bad is absolute nonsense. I can’t even begin to speculate as to what the “good” alternative is. Additionally, what place does sentiment and expression have in a first year drawing student’s training? (Talk about cart before the horse!)

“Working under these disadvantages, we cannot expect ability in drawing from nature. The drawing-book may be needed for examples of historic ornament and design and scientific work ; it or its equivalent may be necessary for examples of freehand drawing, but the moment the student draws from these copies instead of from the object, he is wasting his time and acquiring no practical ability in drawing.”

I won’t even critique this last paragraph. See if you can based on what I’ve explained. It repeats with the same problems listed above.

I hope this helps.

I would also recommend reading my article:

It focuses on some considerations for this type of evaluation.

)

)