This week artist James Gurney shared an essay on a Substack under the heading “Shortcomings of American Art Education.” The essay was written by the American illustrator and painter Edwin Austin Abbey, and it appeared in in the March, 1902 edition of Brush and Pencil magazine.

I can’t tell you how many articles like this I have read but they all have the same problems. While there are indeed a few shiny nuggets of truth, Abbey’s critique of American art education exhibits many of the recurrent issues common in tradition-bound, anecdotal evaluations. Not to be too blunt, but the claims are vague, unsupported by educational research, and frequently framed by comparisons that are also neither substantiated nor well defined. For example, statements like “art education is too fragmentary” or “examinations are too easy” lack any quantifiable reference point—no curriculum data, pedagogical metrics, or assessment standards are cited to contextualize these judgments.

Similarly, appeals to the supposed superiority of “foreign schools” are devoid of comparative analysis or data, rendering the argument as “ungrounded.” Compounding this are problematic conceptual ambiguities, particularly around terms like “talent” or “highest art form,” which are invoked without clarification. The assumption that a rigid filtration of students based on undefined aptitude will yield higher artistic quality contradicts contemporary research in skill acquisition—most notably, the work of K. Anders Ericsson, whose studies on deliberate practice have shown that expert performance arises from structured, effortful training over time, not from innate traits or arbitrary thresholds of entry.

Abbey also perpetuates hierarchical value claims—asserting, for instance, that some works are only “fragments” while large-scale, grand-idea-driven works represent the “highest form” of art. Such assertions are philosophically unfounded and overlook a broad spectrum of valid artistic aims and methodologies. In sum, Abbey’s reflections read more as nostalgic laments than as constructive, evidence-based critiques—and as such, offer little of substance to actually inform pedagogical development or curricular reform.

Give it a read for yourself and see what you think:

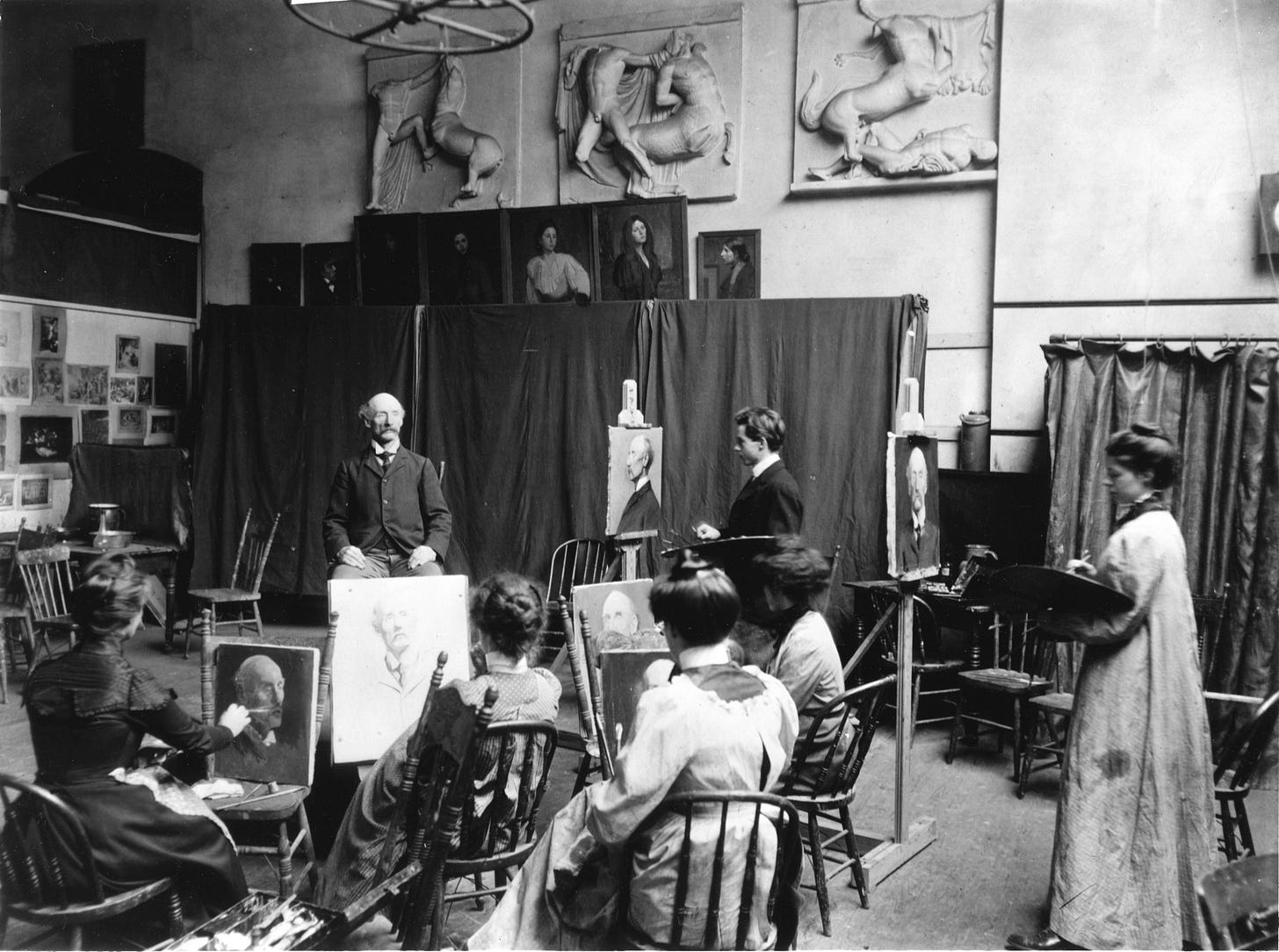

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Portrait Class, 1901

"It seems to me that no one could seriously dispute the fact that a great school of art in America is needed, or that such a school would have the very greatest influence in the development both of the spirit and the practice of art.

As art is now taught in this country, it is too fragmentary. The pupils are not thoroughly grounded. Anyone who wants to study art here can do so. The examinations are too easy. In the foreign schools the examinations are very difficult. The student must know a good deal to pass them. There should be an American school with equally high requirements.

If a young man [or young woman] wants to enter Harvard or Yale, his preparation must be thorough. That is the way it should be with the school of art, for the school of art should really be like a university.

The student, before being admitted to the university, should have passed beyond the elemental stage of study which properly belongs to the grammar-school grade. As it is now in America there is no place where parents who think their son is a genius can send that son to find out that he isn’t a genius. There are very few people who can’t be taught to draw more or less well, but the mere ability to draw does not make an artist.

"There seems to be a desire on the part of a very large number of persons either to become professional artists, sculptors, and painters or to acquire some of the principles of decoration. But there is also widespread ignorance that a thorough grounding in certain facts is absolutely essential to the serious student before he is prepared to avail himself of the experience of others.

Those who wish to study art here are admitted to classes far too leniently. In the schools abroad the entrance examinations are very severe, and by a succession of examinations, the less talented are eliminated. This refers, of course, to the great schools — not to the irresponsible studios, where a model or two is hired and a few painters with a present reputation are engaged to call in occasionally to give advice; to such schools anybody, with no experience whatever, can, by paying a small fee, be admitted.

It has been immensely to the advantage of America that there is nothing for architects abroad which corresponds with the irresponsible painting ateliers referred to. The student of architecture going to Paris, for instance — although my remarks do not apply to Paris alone — can only study his profession by going into the “Beaux Arts.” The entrance examination is very severe, of course, and should be so, but the effect upon the American student is everywhere apparent here, and has given the architects of the United States the great position they occupy to-day.

If the money is provided — and one of the things which surprises me on coming back to America is the amount of money there seems to be — there would seem to be no reason why a great American school of art should not be established and be put in working order within a reasonably short time. A building should be furnished, among other things, with copies of the best examples of art in foreign countries in sculpture, painting, and architecture. There would be little difficulty in acquiring these, although it would take time.

The American Art Federation would be the institution which would most naturally father the work of establishing an American school. And the question of a location for the school would have to be answered by circumstances. It should be in a center, some place where it would be to the advantage of both pupils and instructors to live. The location might be a problem. One would name New York as the obvious place for the school, as the National Academy is there, and the various art societies to which most American artists contribute hold their exhibitions there.

The art ability of Americans is not to be belittled. The best American artists can hold their own anywhere. American art as a whole, however, has the tendency to be preoccupied with problems of a technical nature, such as how to put on paint, and things of that sort. The painting of individual pictures is not art in its highest form. Pictures are only fragments. The great things are works which carry an idea through to completion.

I do not think that the great problems of adapting one subject or composition to its environment is sufficiently studied, if it is studied at all. The three great branches of art — painting, sculpture, and architecture — should be independent. Without a knowledge of the other two, each is incomplete. The restraining influence the study of each one has upon the others is of the greatest importance and of the greatest service.

A school should have, first of all, the great artists of the country as overseers. That is the method pursued in Munich, where the great artists are given studios in the school, and the students are allowed, several days in the week, to consult them about ideas. In addition to the influence of American artists of first rank, the American school might also make arrangements to receive the benefit and advice of prominent foreign artists who are visiting this country from time to time. As to the instructors, there should be many of them, and there is no reason why they should not be drawn from the ranks of American artists.

The curriculum of the school should embrace sculpture, painting, and architecture, and every student should be made to learn something about all three branches of art. There are many Americans who are quite competent to act as instructors, under the supervision of artists of first rank. And the great thing is that the school should have one inspiring head. The advantage of having great artists on the staff, to whom students can have access, lies in the fact that one can learn much more by working with a man than by simply being told what to do, or what not to do. The establishment of the school would mean, primarily, the sifting out of the incapable. It would push forward those who had real talent, and would discourage those without talent.

An art atmosphere is hardly to be spoken of as something which is created; it is rather something which happens. It is a matter of tradition. A whole country grows up to art, and the atmosphere comes gradually into being, one can hardly explain when or how. And a people who have once developed an art atmosphere may degenerate. Take Italy, for example. The Italy of the past was a paradise of art. Rome is an eternal city because of the handiwork which immortal artists have left there, if for no other reason. But take the Italy of to-day—where is its art atmosphere? The average modern Italian likes the worst pictures and loves noise. It would seem as if all the art air had been breathed over there. An art atmosphere is not generated entirely by pictures. The kind of houses men build, and what they put into them; the decorations of public buildings; the beautifying of public parks; the care of the streets, all these things play important parts. In this day, it is not so much the love of pictures as care for vital things which needs to be encouraged.

The generating of an art atmosphere requires a great deal of money, as well as a great deal of good taste on the part of a great many people. Public building decorations of the highest order are so expensive as frequently to make them impossible. The artist who does the work, too, must inevitably make sacrifices. But the man who takes up the profession of art must have higher aims than financial considerations. The painting of an important and thoroughly careful work is much more expensive than most people realize.