Great questions all.

Do you visualize the transitional phase by masking the other parts or by making marks?

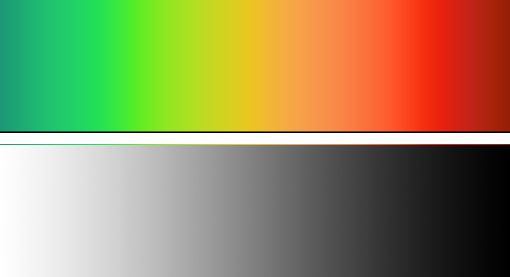

There is a difference between visualizing and creating the actual representation of the transitional phase. My initial categorical perception is just how I perceive the transition. To better understand this—consider these two continuums --one of a section of the electromagnetic spectrum and another of brightness/value. Whereas we might see the latter as an even evolution–the former, also an evolution, is often initially perceived in terms of “chunks” or categories (green/yellow/orange, red, etc…)

I find that this type of categorical chunking takes place when I am first examining a passage as shown above. I see two homogenous regions and a transitional region (more similar to the green, yellow, orange, etc…) It’s just the way my brain finds the most useful information based on my experiences (lifetime and evolutionarily.)

This perception is not the same as how I would execute this (although the process is shaped by the perception.) To mimic the passage seen in the post above I would absolutely establish the anchors that the transition is bound by. No masking would be required as I would actually require the contextual influence of the anchors to better gauge the factors that define the transition.

How do you evaluate concretely the rate of change?

While we cannot objectively determine an absolute lightness visually (our visual system does not work that way), there are many steps we can take to try to emulate the value relationships we experience (a sort of solving for “x” with limited information.) One way is with dynamic squinting which is described here: Scan, Stereo and Squint

Do you suggest diminishing the role of visual short-term memory because you rely more at one point on the parameters you have established before than on comparison side by side which might throw you off (absolute comparison?)

That can definitely be a good strategy. I wouldn’t say that there is any Goldilocks zone to an ideal conceptual and VSTM balance as such an ideal would necessarily be shaped by a goal and chosen process. I do however place emphasis on the conceptual when I am trying to either abstract or to peak-shift something for effect. On the other hand, I place a great deal of emphasis on VSTM when I need to police some of the abstracted imprecision that comes along with an LTM conceptual framework. It’s like I’d obviously rely more on a hammer when more nails are required for a project than screws. It’s just a matter of what is required relative to my intent.

Finally, how do you manage the level of resolution (make smaller and smaller extracts of transitional phases like a recursive procedure)? Knowing that in a real drawing transitional phases can be all over the place in all directions, how do reunify things so as not to get a broken effect?

I believe that this comes with experience. Bringing seemingly disconnected, independently developed sub-units back together can take a great deal of work. In my own process, I let an overall goal of “arrival” govern my process. What I mean by this—for a simple example—I know that if I worked by establishing a long sequence of discreet values for the following gradation, and then tried to tie them together into an evenly-evolving gestalt—it could be a massive amount of work with many likely problems.

Rather, what I would do is establish anchors and begin with a long, overshot anticipatory taper of dark that is meant to receive a long taper of white. I know through experience how dark to go and how far so that an appropriate, subsequent application of white will have the representation “arrive” as intended. So you see, the unification process, for me, is “built in” to the application process. It can easily be seen as unintuitive. This is why we have the gradation block exercise so early in our program–so that artists can understand the parameters of the materials–and how to deploy a strategic sequence of material applications and manipulations so as to facilitate the “arrival” of the appropriate (unified) result.

Here is an image of a gradation block being created in this way (however the initial taper is added prior to the white anchor.) :

Hope this helps!